|

A Scary Look at Data Misrepresentation in Nutritional Science

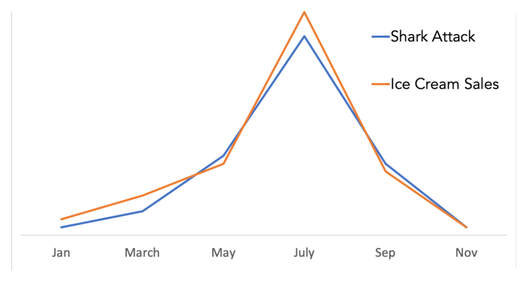

As consumers of information, we are barraged daily with conflicting information, nowhere is this more evident than in nutrition research where the information seems to change from week to week. Why is this the case? We can start with how people eat: are the people in the fake headline above just eating ice cream? Likely they are eating the usual ice cream companions like cones, sprinkles, whipped cream and hot fudge. People follow patterns of eating behavior. It is virtually impossible to take a reductionist view of what people eat and limit it to a single food or nutrient. Then, we can look at how the data is collected. Most often, nutrition research asks people to recall what they ate over a given period of time in the past. Do you recall how much ice cream you ate last summer? Last month? Last week? Was it soft serve or hard? What flavor was it? Was it dairy or dairy-free? Did you add toppings? Was it served in a cup or a cone? What type of cone? …Just how accurate do you think the information collected is? Next, we can examine the participants in the study. How many participants are needed before one can make the observation in our fake headline? 3? 30? 300? What were the demographics of the participants? Was it a diverse group of people (age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographical location, etc.)? If all the participants in our fake headline were 80-year-old Caucasian females living in the Bronx, then it would be nonsensical to the extrapolate trends from this data to anyone other than 80-year-old Caucasian females living in the Bronx. Then, ask yourself, is observation causation? The answer is no. That is a fundamental issue with study design. Much nutrition research is observational. We observe “associations” between variables, but we cannot control unforeseen variables. Let’s take our fake headline: What if the participants in the study ate their ice cream on a sugar cone? How do we know the shark bite wasn't due to the cone and not the ice cream at all? By not measuring the sugar cone as a variable we have made a false association between ice cream and shark attacks. In addition, it is rare in nutrition research to see a “gold standard” randomized control trial (RCT) in nutrition whereby people are randomly assigned to an intervention and a control group. In our fake headline, one group would eat ice cream, one group would not (the control group) but they would both go swimming at the beach. Then we would be able to draw comparisons between the two groups about a shark attack. Sometimes the research comes up flat and nothing of interest is found. These negative results are important! They add to the body of knowledge on a subject. However, negative results aren’t highly sought after and are rarely published. This is referred to as publication bias. What if 10 previous studies found no association between eating ice cream and shark attacks, but because this was a positive result it was the only one published? The body of knowledge suffers as does the information disseminated to the public. It is sad but true, that much research is funded by industries. The nut industry funds much of the research on nuts. The cacao industry funds much of the research on chocolate, and so on. Again, positive findings are more likely to be published, negative findings are repressed. Unfortunately, these positive findings are then used by the government to make nutrition guidelines and recommendations. Researchers are human, they have egos and pride. The careers of scientists are built on their hypotheses, and, like industries, they have a vested interest in positive findings. Disappointingly, research is replete with insidious behavior meant to protect and promote careers. Finally, there is the media; their job is to promote ratings. They are not obligated to properly vet the research (study design, participants, funding, etc.). Additionally, the media fails to properly explain the implication behind the headline (i.e. what does this mean to you?) Where does this leave us, the consumers of information who want to make smart nutrition choices? Do we throw the baby out with the bathwater? Throw our hands up and eat Oreos for breakfast? Pringles for lunch? Not exactly. However, we do have a responsibility to take a look behind the headlines before making dietary decisions that impact our health. Sometimes that may mean getting the original research and using the above to decide if the study is valid for us. Feel free to email Concierge Choice Physicians ([email protected]) with your questions or even send a headline or study to us, and we will be happy to answer your questions.

0 Comments

|

AuthorJohn B. Johnson, MD is a primary care specialist with Batesville Medical Specialties Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed